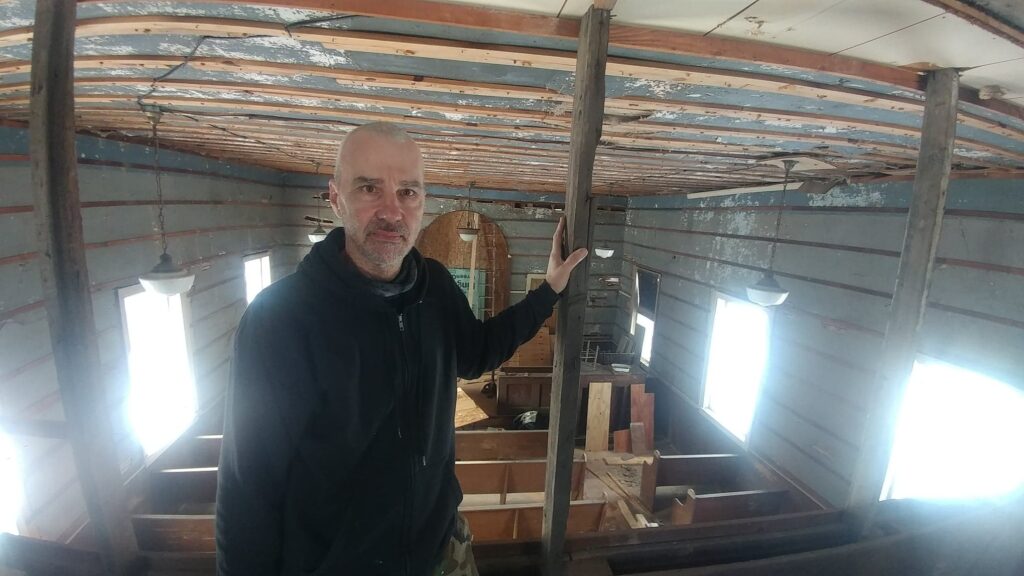

Timmy Montana stands in the upper area of the AME Zion Church in Montrose. He has made it his mission to restore the old, historic church and has, so far, replaced windows and siding. PHOTO BY REGGIE SHEFFIELD

The bell in the AME Zion Church on Berry St., Montrose, was donated to the church by the Lackawanna Co. Railroad in this 1940s. STAFF PHOTO/STACI WILSON

For years the A.M.E. Zion Church on Berry Street in Montrose has fascinated local artist Timmy Montana.

He and others have with some quiet agony watched the long-closed Berry Street church, built in 1859, continue its long slide into disrepair, having last been used regularly as a church in the mid-1970s.

Once a place for former slaves to worship in freedom and peace after surviving the dangerous journey north to freedom and arriving in 19th Century Montrose, the church’s sanctuary, pulpit, roof, walls and floors, speak volumes, but are in serious need of repair.

In fact, as Sherman Wooden of the Center for Anti-Slavery Studies points out, a state Historical and Museum Commission marker on the Montrose town green refers to Susquehanna County as “an early Abolitionist center and stop on the Underground Railroad.”

So one day Montana took it upon himself to start fixing it. Didn’t ask anyone. Didn’t tell anyone. He just broke in.

“I broke into this church, initially, and put my own lock on it. Some people would consider that a crime” Montana said, peering out a church window on a sunny but very snowy February day.

Why would someone take on such a monumental task, Montana was asked.

He paused for a few moments to consider the question and looked at the floor of the small church tucked away on a quiet side street off of Church and Spruce Streets in the town’s southwest corner.

“Their integrity, their perseverance, their strength; their brotherly love, what they had to achieve to get to this, to get to freedom, it’s just inspiring,” he said. “And this is an emblem of that, this church. So, I took it upon myself to resurrect it, let it shine, let it give hope. It really is a symbol of hope, is what it is. It really is a symbol of hope, isn’t it, this church?”

Years ago, Montana met Wooden at his studio. Like Montana, Wooden and his organization, the Montrose-based Center for Anti-Slavery Studies, has long had a focus on the A.M.E. Zion Church. According to Wooden, the A.M.E. Zion Conference has not paid attention to the church for years. Through the years, C.A.S.S. has kept up payments on the taxes and the electricity. Their attempts to contact the conference never produced any response.

Montana recalls one of his conversations with Wooden eventually getting around to the condition of the church’s roof and then going something like this, with Wooden asking him, “Tim, I know you’re inspired by the AME Church, but do you know it’s raining in there right now? I said, ‘Oh, no . . . ’ ”

Montana and Wooden have since gotten over his trespass and Wooden now has his own key.

Through his work with the C.A.S.S, Wooden knew that in the 1860s the A.M.E. Zion Church served as a focal point in the lives of Montrose’s small African American community of mostly escaped slaves.

According to the article “Finding Sanctuary at Montrose,” by William Kashatus published in the Winter 2007 edition of Pennsylvania Heritage magazine, by 1850, 162 African Americans lived in Susquehanna County, which then had a total population of 28,688.

In 1847, records show, abolitionist David Post deeded a 3,280 square foot lot on Berry Street to former slave Charles Hammond, who in turn turned the property over in 1859 to “the Trustees of the African Methodist Church.”

But by the 21st Century, when Montana and Wooden finally had their conversation in Montana’s studio about the condition of the church, the intervening years had continued to take their toll, money was even shorter, and Wooden had become even more worried.

He had good reason to worry. Late last year, Montrose Borough officially condemned the church building and posted notices on the property, emphasizing that they were primarily concerned with the exterior of the building as the interior is not currently used for gatherings. Meetings and correspondence between Wooden and borough officials have since laid out an improvement plan which includes as its first items of business the repair of the roof and windows (some of which has already been accomplished) and painting the church exterior. Borough officials also reached out to the A.M.E. Zion Conference about the church but got no response.

“The church is a historic staple in Montrose, and they would hate to see anything happen to it due to deterioration,” borough secretary Lillian T. Senko wrote Wooden and C.A.S.S. in December.

Wooden said plans for the church include using it to depict the story of people of color in Northeastern Pennsylvania, overseen by the Center for Anti-Slavery Studies.

Besides Montana, others have reached out to lend a helping hand.

A GoFundMe page was started by Tom Follert and has already collected over $8,000 and other donations have reached Wooden directly. Follert got involved after seeing Montana post the careful progress of his renovations on Facebook.

“Being somebody who grew up in Montrose I think it’s really important that we work to restore historical buildings and that one certainly holds a lot of history that I think we’ve forgotten about,” said Follert said of the A.M.E. Zion Church.

To donate to the restoration project, visit: Restore the AME Zion Church in Montrose at https://www.gofundme.com/f/26esk8d8g0.

More on the AME Zion Church restoration project in Montrose, as well as church history, will be published in the upcoming edition of Living – Susquehanna & Wyoming Counties. Find it on newsstands in late March.

Be the first to comment on "Restoring the AME Zion Church"